One in a succession of winter storms is still producing heavy rain, snow and high winds in parts of New England after unleashing severe thunderstorms with embedded tornadoes across the Southeast U.S. on Jan 9 2024. At the storm’s peak, 196 million people were under wind advisories, warnings and watches, including entire states from Florida to Maine, as a powerhouse cold front associated with it pushed east causing power outages and disrupting travel across the U.S. The era of simultaneous climate disasters is here to stay. Rebecca Falconer, Andrew Freedman

The climate impacts this past summer are a mere preview of what the planet will look like

after warming at least 1.5°C (2.7°F) above preindustrial levels. That has already been briefly achieved now bolstered by human-caused climate change and an El Nino event. The picture that emerges is deadly, expensive and concerning. Most observers did not have these extreme weather events, all happening at the same time. During Canada’s worst wildfire season on record, the largest city in the Northwest Territories was completely evacuated, while Kelowna in British Columbia was threatened by advancing flames as well.

At the same time, Tropical Storm Hillary made a rare incursion into California, yielding flash flooding, mudslides, debris flows and nearly unheard-of rainfall rates in the middle of the desert. The storm is consistent with studies showing increasing precipitation extremes overall with climate change, and a trend toward wetter hurricanes. Meanwhile, in the middle of the country, an infernal heat dome was spiking heat indices to staggering territory between the Twin Cities and Houston. Some areas’ heat waves, primarily among parts of Texas, Louisiana and South Florida, only fully relented with the sudden advent of winter.

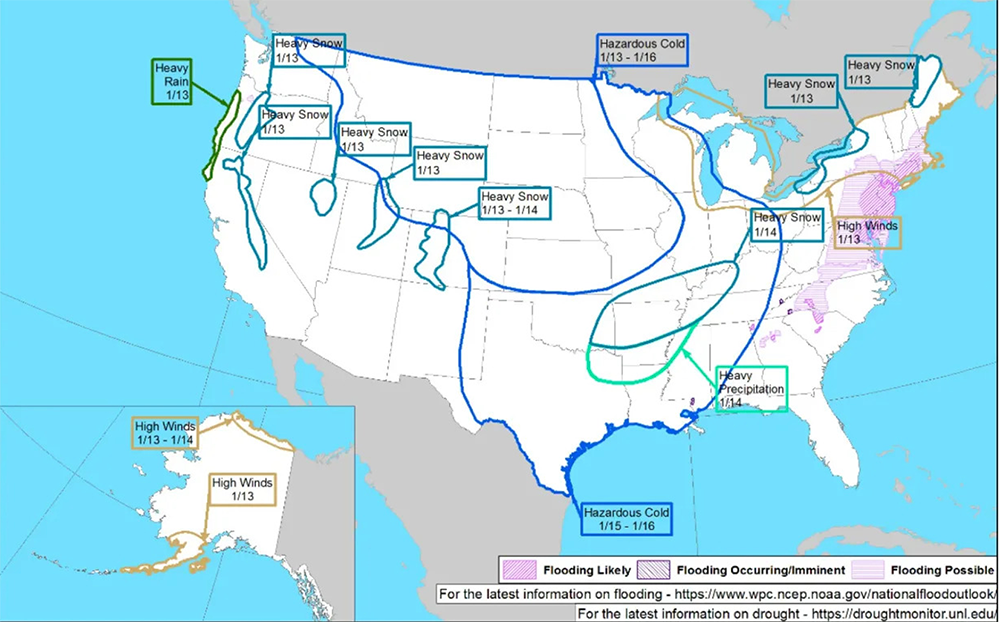

FEMA’s national map showing hazardous weather in January of 2024, including variations of snow, wind, cold, rain and floods affecting most of the country.

No single image could fully capture the confluence of extreme weather events that is disrupting the United States this week, buffeting the country from coast to coast with snowstorms, intense flooding, high winds and even tornadoes. Each weekday morning at precisely 8:30, the Federal Emergency Management Agency releases what it calls its “hazards outlook” map, designed to show the threats expected in the coming days. The goal is to help emergency managers and other officials around the country prepare for what’s headed their way. On Monday, FEMA’s hazard map showed areas of heavy rain, freezing rain, heavy snow, heavy precipitation, hazardous cold, high winds and general severe weather. Seemingly just four of the 50 states were not facing some type of worrisome hazard. By Thursday, the picture had somehow become even worse. In addition to heavy snow, heavy rain and high winds, a flood risk extended from the border between Maine and New Hampshire, all the way to Alabama.

It wasn’t always like this. During the second week of January a decade ago, for example, FEMA’s hazard maps were simple by comparison: High winds in the upper plains, heavy rain around the Florida panhandle, small pockets of flooding, drought in parts of the West. That pattern — localized concerns in parts of the country, with much of the map showing no hazards — was much the same during this week five years ago.

Of course, severe winter storms are nothing new, and no single weather event can automatically be attributed to climate change. But as the planet warms, the atmosphere can hold more water, which makes severe weather more likely.

Jeremy Greenberg, director of the operations division in FEMA’s Response Directorate, has stated “The duration, frequency and intensity of the hazards is increasing over time, It’s becoming a little more commonplace that this map looks like this, and we’ve got a variety of hazards.”

Disasters in the United States used to follow a fairly predictable pattern. Winter brought snow; spring brought floods and the summer and early fall delivered hurricanes, with hopefully some downtime before the cycle would start again. Now, those seasonal shifts are becoming less meaningful. “A snowstorm in the Rockies in the winter is very normal,” he said. “A tornado in Alabama in the winter is not.” Greenberg sees a silver lining in the relentless parade of severe weather: It can grab the attention of Americans, helping them understand that the world is changing around them and they need to be ready.

“The hazards are real,” Greenberg said. c.2024 The New York Times Company

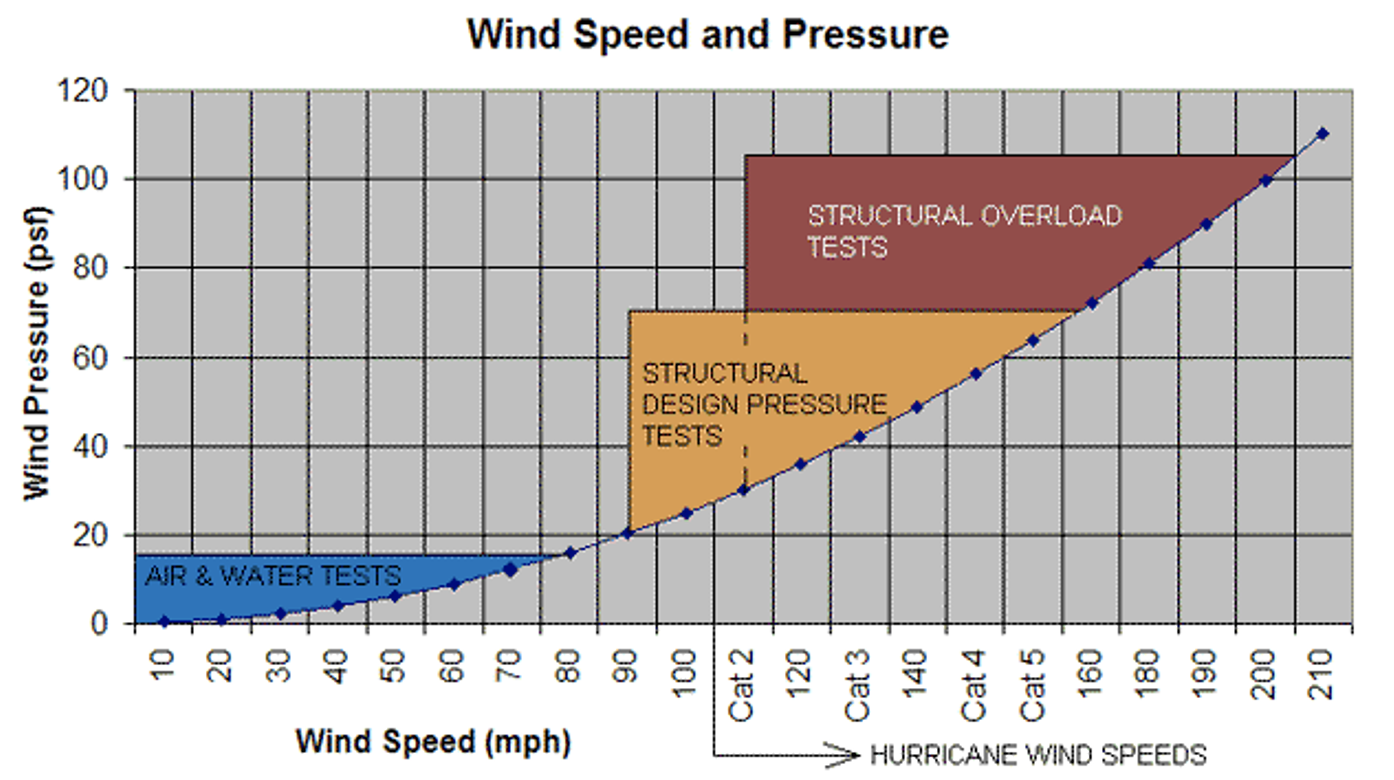

Closed cell spray polyurethane foam (SPF), when applied in walls, ceilings, floors and on the roof, ranging in densities from 2.0 to 3.5 pounds per cubic foot (PCF), protects the structure from serious and costly damage (see following ratings and wind speed charts). It can alleviate concerns of builders, contractors and facility owners due to the increasing number and intensity of severe storms in the United States and the resulting damage that may be incurred to commercial and residential structures.

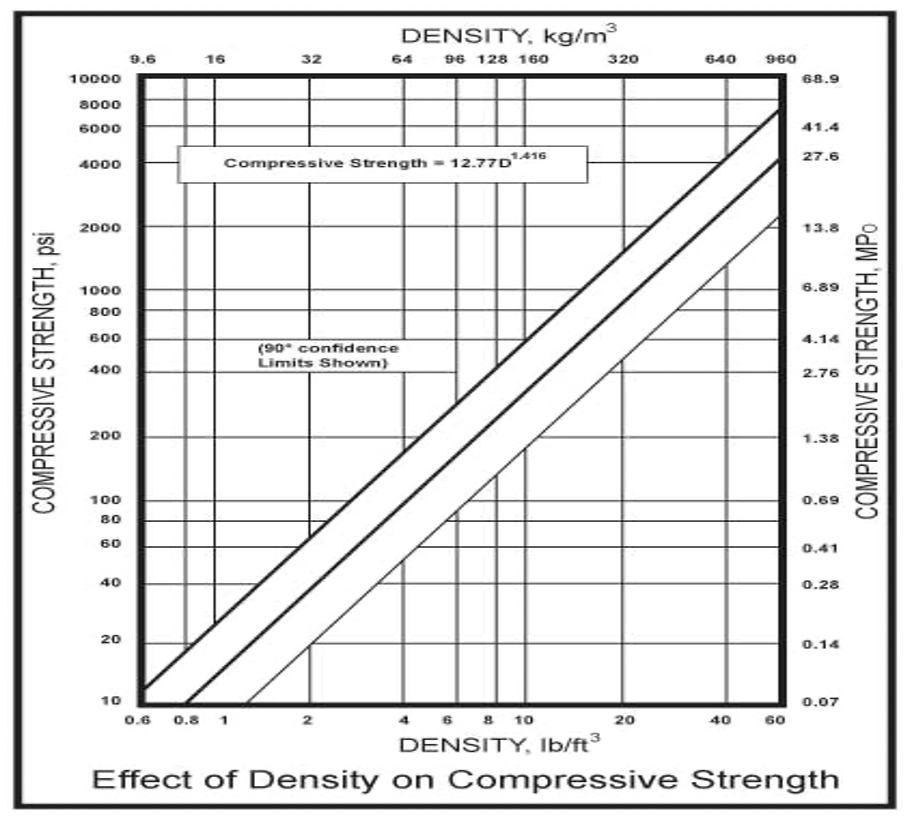

Structural Strength and Wind Resistance – The application of closed cell SPF in above grade walls and roofs increases the structural strength of buildings and assists with wind resistance. When installed, closed cell SPF provides a waterproof monolithic structure essentially gluing the assembly together which reduces the potential for movement and adds a compressive strength ranging from 50-90 PSI (7,920 – 12,960 psf) and tensile strength ranging from 65-100 PSI (9,360 – 14,400 psf), depending on the density of the foam. Closed cell SPF is typically applied ranging in densities from 2.0 – 3.5 lbs/ft3and thicknesses from 2 to 8 in. The thicker the foam the greater level of protection available. This performance with their associated ratings will protect structures from extreme weather wind and hail events and are well above snow fall accumulation weights. Special bracing for wind resistance is not required for strengthening purposes when using closed cell spray foam in walls. The tensile strength of 3.0 lb. foam is approximately 100 psi or 10-15 psi higher than the depicted compressive strength in the above graph, plus it forms a monolithic structure which greatly resists external shearing forces and acts to maintain the structural integrity of buildings during extreme weather events in hot or cold environments.

It also provides greatly improved energy efficiency, a stable interior environment and waterproofing and flood resistance to your building. Closed-cell foams do require specialized equipment and professional installation for proper application and performance.

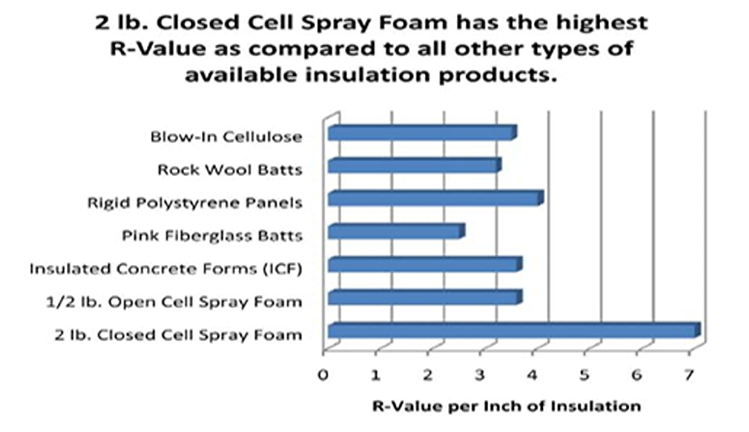

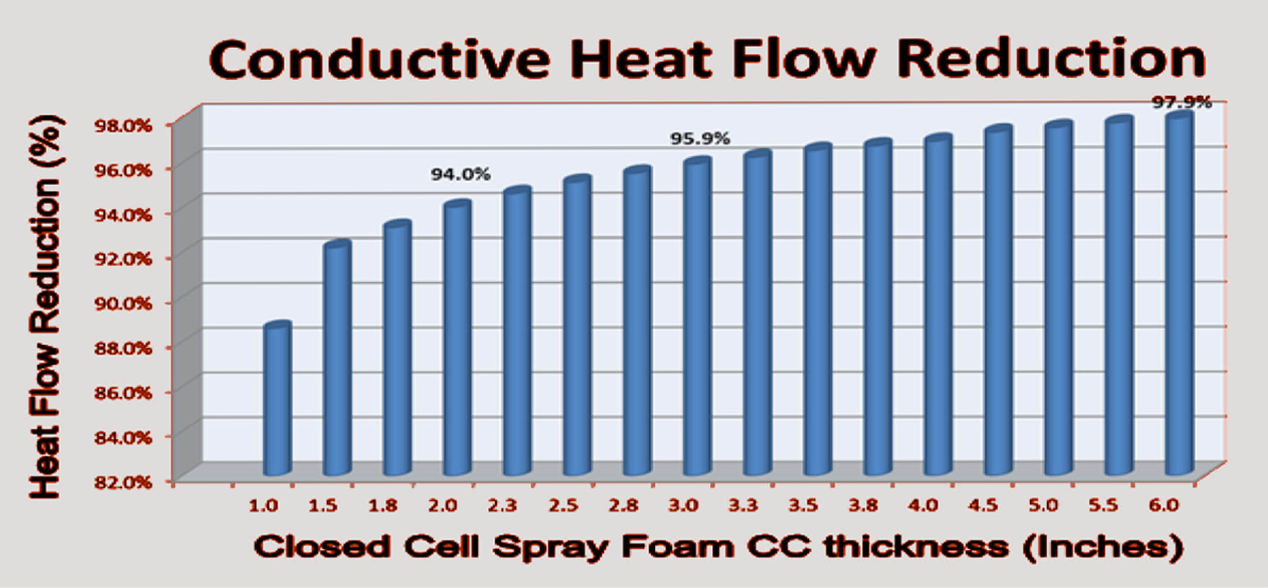

The following is a graphic of the thermal efficiency of closed-cell SPF per inch of coverage. Closed-cell foam can produce energy efficient ratings in excess of 95%, with 2.5 inches of foam. In addition, closed-cell foam is highly water and flood resistant and does not lose its insulating structural properties if wet.

Several studies done at Texas A&M University and a school district in Southern Texas indicate that the energy savings alone paid for the roofing system and all the other benefits such as the following were essentially included:

- Storm damage resistant along with easy repair since damage, if any, is localized.

- Minimal maintenance.

- Stronger more sustainable buildings. Especially important in areas of extreme weather

- Year round comfort of interior.

- Roof contouring to eliminate drainage issues and water ponding.

- Easily renewed with cleaning and/or additional coatings to prevent weathering damage to roof.

- 5-20 year renewable warranties available.